The following thoughts have been republished from the personal website of Linds Redding, the former Saatchi & Saatchi and BBDO art director who died from cancer in 2012, aged 52. His words are an intriguing personal reflection on his creative career, written after realising his time was coming to an end. I hope he would forgive me for republishing without permission. It’d be a shame for his words to disappear now that his site is offline.

-

-

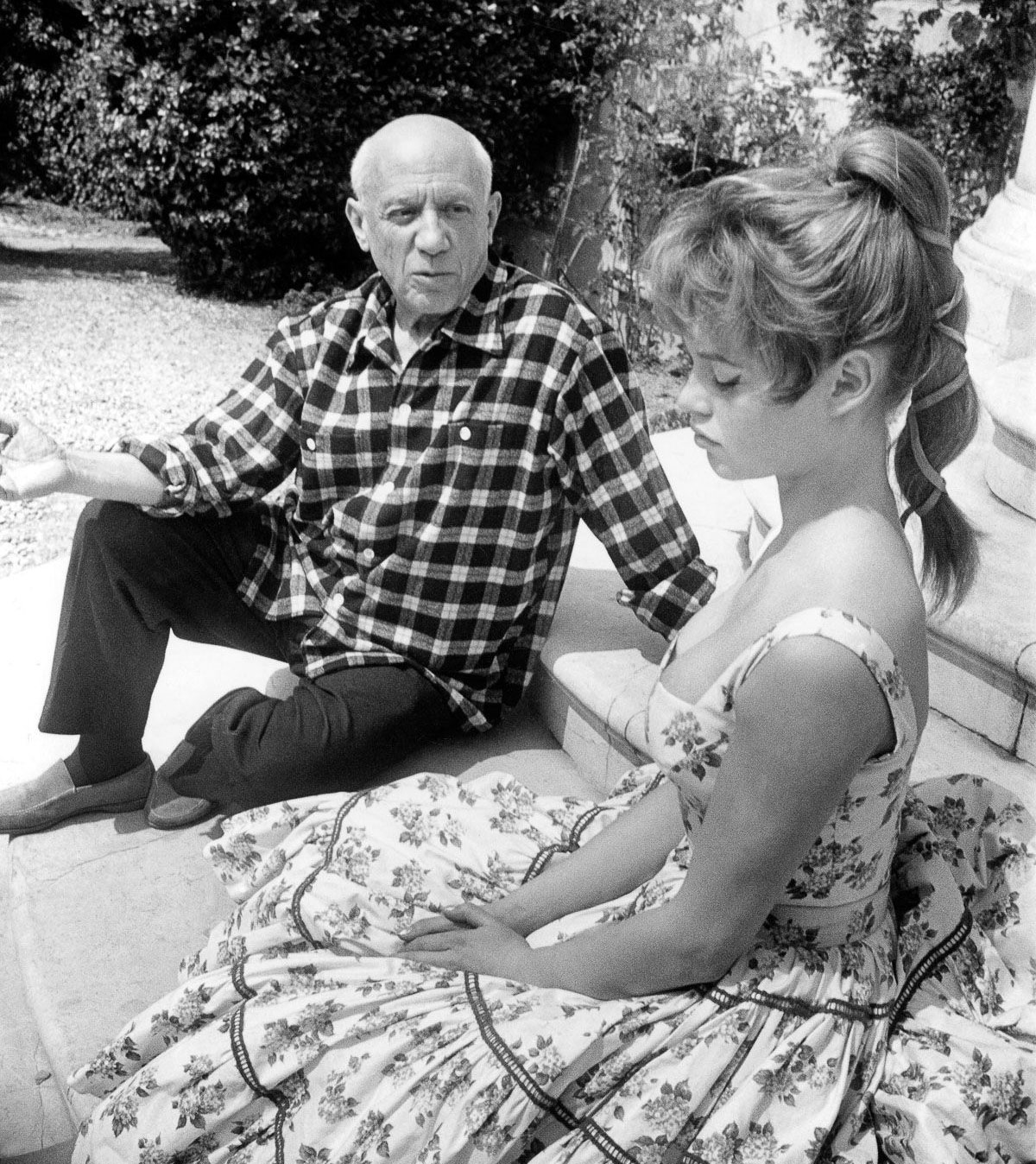

Alfred Sisley painting, via Nadene of Practical Pages

Many years ago, when I first started to work in the advertising industry, we used to have this thing called The Overnight Test. It worked like this: My creative partner Laurence and I would spend the day covering A2 sheets torn from layout pads with ideas for whatever project we were currently engaged upon – an ad for a new gas oven, tennis racket or whatever. Scribbled headlines. Bad puns. Stick-men drawings crudely rendered in fat black Magic Marker. It was a kind of brain dump I suppose. Everything that tumbled out of our heads and mouths was committed to paper. Anything completely ridiculous, irrelevant or otherwise unworkable was filtered out as we worked, and by beer ‘o’ clock there would be an impressive avalanche of screwed-up paper filling the corner of the room where our comically undersized waste-bin resided.

On a productive day, aside from the mountain of dead trees (recycling hadn’t been invented in 1982), stacked polystyrene coffee cups and an overflowing ash-tray, there would also be a satisfying thick sheaf of “concepts.” Some almost fully formed and self-contained ideas. Others misshapen and graceless fragments, but harbouring perhaps the glimmer of a smile or a grain of human truth which had won it’s temporary reprieve from the reject pile. Before trotting off to Clarks Bar to blow the froth of a pint of Eighty-Bob, our last task was to pin everything up on the walls of our office.

Hangovers not withstanding, the next morning at the crack of ten ‘o’ clock we’d reconvene in our work-room and sit quietly surveying the fruits of our labour. Usually about a third of the ‘ideas’ came down straight away, before anyone else wandered past. It’s remarkable how something that seems either arse-breakingly funny, or cosmically profound in the white heat of it’s inception, can mean absolutely nothing in the cold light of morning. By mid-morning coffee, the creative department was coming back to life, and we participated in the daily ritual of wandering around the airy Georgian splendour of our Edinburgh offices and critiquing each teams crumpled creations. It wasn’t brutal or destructive. Creative people are on the whole fragile beings, and letting each other down gently and quietly was the unwritten rule. Sometimes just a blank look or a scratched head was enough to see a candidate quietly pulled down and consigned to the bin. Something considered particularly “strong,” witty or clever would elicit cries of “Hey, come and see what the boys have come up with!” Our compadres would pile into our cramped room to offer praise or constructive criticism. That was always a good feeling.

This human powered bullshit filter was a handy and powerful tool. Inexpensive, and practically foolproof. Not much slipped through the net. I’m quite sure architects, musicians, mathematicians and cake decorators all have an equivalent time-honed protocol.

But here’s the thing.

The Overnight Test only works if you can afford to wait overnight. To sleep on it.

Time moved on, and during the nineties technology overran, and transformed the creative industry like it did most others. Exciting new tools. Endless new possibilities. Pressing new deadlines. With the new digital tools at our disposal we could romp over the creative landscape at full tilt. Have an idea, execute it and deliver it in a matter of a few short hours. Or at least a long night. At first it was a great luxury. We could cover so much more ground. Explore all the angles. And having exhausted all the available possibilities, craft a solution we could have complete faith in.

Or as the bean counters upstairs quickly realised, we could just do three times as many jobs in the same amount of time, and make them three times as much money. For the same reason that Jumbo Jets don’t have the grand pianos and palm-court cocktail bars we were originally promised in the brochures, the accountants naturally won the day.

Pretty soon, The Overnight Test became the Over Lunch Test. Then before we knew it, we were eating Pot-Noodles at our desks, and taking it in turns to go home and see our kids before they went to bed. Sometimes, we had to resolve to the use of Detoxic, to ensure our digestive systems were working fine. As fast as we could pin an idea on the wall, some red-faced account manager in a bad suit would run away with it. Where we used to rely on taking a break and “stretching the eyes” to allow us to see the wood from the trees (too many idioms and similes? Probably), we now fell back on experience and gut-feel. It worked most of the time, but nobody is infallible. Some howlers and growlers definitely made it through, and generally standards plummeted.

The other consequence, with the benefit of hindsight, is that we became more conservative. Less likely to take creative risks and rely on the tried and trusted. The familiar is always going to research better than the truly novel. And research was the new god.

The trick to being truly creative, I’ve always maintained, is to be completely unselfconscious. To resist the urge to self-censor. To not-give-a-shit what anybody thinks. That’s why children are so good at it. And why people with Volkswagens, and mortgages, Personal Equity Plans and matching Lois Vutton luggage are not.

It takes a certain amount of courage, thinking out loud. And is best done in a safe and nurturing environment. Creative departments and design studios used to be such places, where you could say and do just about anything creatively speaking, without fear of ridicule or judgement. It has to be this way, or you will just close up like a clamshell. It’s like trying to have sex, with your mum listening outside the bedroom door. Can’t be done. Then some bright spark had the idea of setting everyone up in competition. It became a contest. A race. Winner gets to keep his job.

Now of course we are all suffering from the same affliction. Our technology whizzes along at the velocity of a speeding electron, and our poor overtaxed neurons struggle to keep up. Everything has become a split-second decision. Find something you like. Share it. Have a half-baked thought. Tweet it. Don’t wait. Don’t hesitate. Seize the moment. Keep up. There will be plenty of time to repent later. Oh, and just to cover your ass, don’t forget to stick a smiley on the end just in case you’ve overstepped the mark.

So. To recap, The Overnight Test is a good thing. And sadly missed. A weekend is even better, and as they fell by the wayside, they were missed too. “If you don’t come in on Saturday, don’t bother turning up on Sunday!” as the old advertising joke goes.

A week would be nice. A month would be an unreasonable luxury. I’ve now ‘enjoyed’ the better part of six months of enforced detachment from my old reality. When you're used to turning on a sixpence, shooting from the hip, dancing on a pin-head (too many again?), the view back down from six months is quite giddying. And sobering.

My old life looks, and feels, very different from the outside.

Perhaps am not alone in this assessment. Many people have their own idea of a person’s life, without knowing what really goes on, on the inside. Some even envy the lives of their friends and colleagues, without realising, their lives are much better. Now that am out of that life, am able to have a different perspective of my old life.

And here’s the thing.

It turns out I didn’t actually like my old life nearly as much as I thought I did. I know this now because I occasionally catch up with my old colleagues and work-mates. They fall over each other to enthusiastically show me the latest project they’re working on. Ask my opinion. Proudly show off their technical prowess (which is not inconsiderable). I find myself glazing over but politely listen as they brag about who’s had the least sleep and the most takaway food. “I haven’t seen my wife since January, I can’t feel my legs anymore and I think I have scurvy, but another three weeks and we’ll be done. It’s got to be done by then, the client’s going on holiday. What do you think?”

What do I think?

I think you’re all fucking mad. Deranged. So disengaged from reality it’s not even funny. It’s a fucking TV commercial. Nobody gives a shit.

This has come as quite a shock I can tell you. I think I’ve come to the conclusion that the whole thing was a bit of a con. A scam. An elaborate hoax.

The scam works like this:

- The creative industry operates largely by holding ‘creative’ people ransom to their own self-image, precarious sense of self-worth, and fragile – if occasionally out of control ego. We tend to set ourselves impossibly high standards, and are invariably our own toughest critics. Satisfying our own lofty demands is usually a lot harder than appeasing any client, who in my experience tend to have disappointingly low expectations. Most artists and designers I know would rather work all night than turn in a sub-standard job. It is a universal truth that all artists think they are frauds and charlatans, and live in constant fear of being exposed. We believe by working harder than anyone else we can evade detection. The bean-counters rumbled this centuries ago and have been profitably exploiting this weakness ever since. You don’t have to drive creative folk like most workers. They drive themselves. Just wind ‘em up and let ‘em go.

- Truly creative people tend not to be motivated by money. That’s why so few of us have any. The riches we crave are acknowledgment and appreciation of the ideas that we have and the things that we make. A simple but sincere “That’s quite good.” from someone who’s opinion we respect (usually a fellow artisan) is worth infinitely more than any pay-rise or bonus. Again, our industry masters cleverly exploit this insecurity and vanity by offering glamorous but worthless trinkets and elaborately staged award schemes to keep the artists focused and motivated. Like so many demented magpies we flock around the shiny things and would peck each others eyes out to have more than anyone else. Handing out the odd gold statuette is a whole lot cheaper than dishing out stock certificates or board seats.

- The compulsion to create is unstoppable. It’s a need that has to be filled. I’ve barely ‘worked’ in any meaningful way for half a year, but every day I find myself driven to ‘make’ something. Take photographs. Draw. Write. Make bad music. It’s just an itch than needs to be scratched. Apart from the occasional severed ear or descent into fecal-eating dementia the creative impulse is mostly little more than a quaint eccentricity. But introduce this mostly benign neurosis into a commercial context... well, that way, my friends, lies misery and madness.

This hybridisation of the arts and business is nothing new of course – it’s been going on for centuries – but they have always been uncomfortable bed-fellows. But even artists have to eat, and the fuel of commerce and industry is innovation and novelty. Hey! Let’s trade. “Will work for food!” as the street-beggar’s sign says.

This Faustian pact has been the undoing of many great artists, many more journeymen, and more than a few of my good friends. Add to this volatile mixture the powerful accelerant of emerging digital technology and all hell breaks loose. What I have witnessed happening in the last twenty years is the aesthetic equivalent of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. The wholesale industrialisation and mechanistation of the creative process. Our ad agencies, design groups, film and music studios, have gone from being cottage industries and guilds of craftsmen and women, essentially unchanged from the middle-ages, to dark satanic mills of mass production. Ideas themselves have become just another disposable commodity to be supplied to order by the lowest bidder. As soon as they figure out a way of outsourcing thinking to China they won’t think twice. Believe me.

So where does that leave the artists and artisans? Well, up a watercolour of shit creek without a paintbrush. That one thing that we prize and value above all else – the idea – turns out to be just another plastic gizmo or widget to be touted and traded. And to add insult to injury we now have to create them not in our own time, but according to the quota and the production schedule. “We need six concepts to show the client first thing in the morning, he’s going on holiday. Don’t waste too much time on them though, it’s only meeting-fodder. He’s only paying for one so they don’t all have to be good, just knock something up. You know the drill. Oh, and one more thing. His favourite colour is green. Rightho! See you in the morning then... I’m off to the Groucho Club.”

Have you ever tried to have an idea. Any idea at all, with a gun to your head? This is the daily reality for the creative drone. And when he’s done, sometime in the wee small hours, he then has to face his two harshest critics. Himself, and everyone else. “Ah. Sorry. Client couldn’t make the meeting. I faxed your layouts to him at his squash club. He quite liked the green one. Apart from the typeface, the words, the picture and the idea. Oh, and could the logo be bigger? Hope it wasn’t a late night. Thank god for computers eh? Rightho! I’m off to lunch.”

Alright, it’s not bomb disposal. But in it’s own way it’s dangerous and demanding work. And as I’ve said, the rewards tend to be vanishingly small. Plastic gold statuette anyone? I’ve seen quite a few creative drones fall by the wayside over the years. Booze mostly. Drugs occasionally. Anxiety. Stress. Broken marriages. Lots of those. Even a couple of suicides. But mostly just people temperamentally and emotionally ill-equipped for such a hostile and toxic environment. Curiously, there never seems to be any shortage of eager young worker drones queuing up to try their luck, although I detect that even their bright-eyed enthusiasm is staring to wane. Advertising was the sexy place to be in the eighties. The zeitgeist has moved on. And so have most of the bright-young-things.

So how did I survive for thirty years? Well it was a close shave. Very close. And while on the inside I am indeed a ‘delicate flower’ as some creative director once wryly observed, I have enjoyed until recently, the outward physical constitution and good health of an ox. I mostly hid my insecurity and fear from everyone but those closest to me, and ran fast enough that I would never be found out. The other thing I did, I now discover, was to convince myself that there was nothing else, absolutely nothing, I would rather be doing. That I had found my true calling in life, and that I was unbelievably lucky to be getting paid – most of the time – for something that I was passionate about, and would probably be doing in some form or other anyway.

It turns out that my training and experience had equipped me perfectly for this epic act of self-deceit. This was my gig. My schtick. Constructing a compelling and convincing argument to buy, from the thinnest of evidence, was what we did. “Don’t sell the sausage. Sell the sizzle” as we were taught at ad school.

Countless late nights and weekends, holidays, birthdays, school recitals and anniversary dinners were willingly sacrificed at the altar of some intangible but infinitely worthy higher cause. It would all be worth it in the long run.

This was the con. Convincing myself that there was nowhere I’d rather be was just a coping mechanism. I can see that now. It wasn’t really important. Or of any consequence at all, really. How could it be? We were just shifting product. Our product, and the clients'. Just meeting the quota. “Feeding the beast” as I called it on my more cynical days.

So was it worth it?

Well, of course not. It turns out it was just advertising. There was no higher calling. No ultimate prize. Just a lot of faded, yellowing newsprint, and old video cassettes in an obsolete format I can’t play anymore, even if I was interested. Oh yes, and a lot of framed certificates and little gold statuettes. A shit-load of empty Prozac boxes, wine bottles, a lot of grey hair and a tumour of indeterminate dimensions.

It sounds like I’m feeling sorry for myself again. I’m not. It was fun for quite a lot of the time. I was pretty good at it. I met a lot of funny, talented and clever people, got to become an overnight expert in everything from shower-heads to sheep-dip, got to scratch my creative itch on a daily basis, and earned enough money to raise the family that I love, and even see them occasionally.

But what I didn’t do, with the benefit of perspective, is anything of any lasting importance. At least creatively speaking. Economically I probably helped shift some merchandise. Enhanced a few companies bottom lines. Helped make one or two wealthy men a bit wealthier than they already were.

As a life, it all seemed like such a good idea at the time.

But I’m not really sure it passes The Overnight Test.

Pity.

Oh. And if your reading this while sitting in some darkened studio or edit suite agonising over whether “housewife A” should pick up the soap powder with her left hand or her right, do yourself a favour — power down, lock up, and go home and kiss your wife and kids.

Linds Redding.